Fenwick Yellowley Hedley

By Carl L. Stanton

F. Y. Hedley came to South Macoupin county following the Civil War, having enlisted while a resident of Carlinville. He spent 33 years

|

Hedley was editor and publisher of the Bunker Hill Gazette for over 30 years, from 1866 until 1898. Only five feet three inches tall and slight of build, he was a hero in the Civil War and delighted in writing and telling of his adventures in later years. He was also an accomplished speaker, and a musician of note. In addition to his newspaper writing, he was author of a book describing the action during the march from Atlanta to the sea, and other historical volumes.

Hedley was born in Scotland on March 2, 1844, a son of Fenwich Yellowley Hedley, and was named for his father, thus the F. Y. he always went by. His local column in the Gazette was called "Specs" and that is the way he referred to himself. These columns contained some exceptionally good writing.

Hedley inherited his combativeness from his father, who was a minister of the Baptist church. For some years the senior Hedley was a crusader for temperance in England and Scotland. On one of these crusades in 1847, he took ill and died from exposure, leaving his wife and two children. His widow remarried, this time to Wilson W. Pattison, and in 1852 they came to America.

They came to New Orleans and up the Mississippi to St. Louis, where they settled for a time before moving on to Carlinville. Hedley was then eight years old. He went to school in St. Louis, and then Blackburn University at Carlinville.

After Blackburn, he worked at the Carlinville Democrat, where he learned the printing trade. He was already an accomplished typesetter by the age of 17, when he joined the army. He later wrote of working in the Democrat office when Abraham Lincoln came to visit the publisher. On one occasion Lincoln spoke to him about his reading and education, and impressed young Hedley tremendously. Hedley also heard Lincoln speak more than once in Carlinville and during the campaign of 1860 went with other men from Carlinville to Springfield where they took part in a huge political rally for Lincoln. He said they marched in a daytime parade carrying signs and a nighttime parade carrying torches. It was the custom in those days to carry torches while parading for their party's candidates. In Hedley's case, it was always the Republican party. Lincoln's party could do no wrong, in his eyes. Hedley finished his schooling and learned printing before entering the army at age 17. And he was well educated, too. He often quoted the Greek and Roman classics and included Latin quotes in his writing, evidence of a classical education.

Because of his acquaintance with Lincoln, he hoped for an appointment to West Point following Lincoln's election, but after the outbreak of war he was much too impatient for that, and enlisted in the army.

On Aug. 24, 1861 he enlisted in Company C, 32nd Regiment, Illinois Volunteers, commanded by Col. John Logan of Carlinville. He was several months too young and two inches too short to enlist as a soldier so he enlisted as a musician, or drummer boy. By arrangement with his regimental commander, he was immediately made a private and trained and fought with his older and larger comrades. His regiment was attached to the old 4th Division of the Army of the Tennessee, under General Grant, and later to the 17th Corps. He first took part in the battle of Pittsburg Landing and Shiloh and then in other engagements of the Tennessee River campaigns, including Corrinth, Miss. He was at Vicksburg and Alatoona. His book, "Marching Through Georgia", details his experiences in the Georgia and Carolinas campaigns. He ended up a general's adjutant and first lieutenant, brevetted captain after his retirement at age 21.

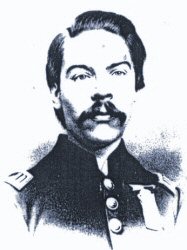

His original enlistment was for three years, but late in 1863 he re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer. I think he might have received a furlough at that time and returned home for there is a picture of him in uniform at age 20, taken by a Carlinville photographer, and he would have been that age at the end of his three-year enlistment. He didn't write of his experiences before that. I believe it is because he didn't keep a journal until he became an officer. In his book on the march through Georgia, he often referred to his journal.

Hedley remained a private or at least a non-commissioned officer, until then, as nearly as we can tell. That is when he re-enlisted as a veteran, and we think when he was commissioned a lieutenant. He came home to Carlinville for a furlough at that time and then returned to his regiment. His regiment took part in the Atlanta campaigns. He was part in the march with Sherman from Atlanta to the Sea, and later wrote his book about the campaign, which was commended by many, including General Sherman. These comments follow the text of newspaper articles which were the basis of the book and which are printed in this book.

Early in 1865, on the recommendation of his division commander, Gen. W. W. Belknap, who was afterwards Secretary of War, and Gen. Frank P. Blair, Hedley was commissioned lieutenant by President Lincoln, and was assigned to staff duty as assistant adjutant general of the 3rd Brigade, 4th Division, 17th Corps. He acted as such during the campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas until the end of the war.

After the war he and his unit were shipped to the west to fight Indians. Many of the soldiers deserted, believing they should have been discharged when the war ended, and they blamed their commanding officer, Gen. Stolbrand, for their not being mustered out of service. They even tried to murder him, and Hedley kept guard over the tent they shared while the general slept. It was proved later that the general was not to blame. Hedley talked the men into staying with the army rather than deserting en masse and drew up a petition they all signed and sent to the war department. The unit was stopped before reaching Utah, and brought back to Springfield, Ill. where it was mustered out of service on Oct. 24, 1865.

That's when Hedley came to Bunker Hill and started his career as a newspaper-man.

He began work Jan. 1, 1866 and the first issue appeared Jan. 19. He composed all the type for that edition. He was always too small for the heavier press work.

Major A. E. Edwards was founder and owner of the Union Gazette, but he soon moved on to bigger things, ending up as owner of a paper in Fargo, Dakota Territory, and was a politician there. Before the war Edwards had run a newspaper at Gillespie and it was this equipment which went into the paper at Bunker Hill. Hedley said later it was already worn out and soon replaced.

In February, 1867 Hedley and Dr. A. R. Sawyer of Bunker Hill bought the paper from Edwards, and on Dr. Sawyer's death the following year, Hedley became sole owner and remained such until 1898. He was 24 years old. He renamed the Union Gazette the Bunker Hill Gazette.

Hedley was very active in the GAR and attended meetings throughout the midwest in connection with it. He attended conventions of the Association of the Army of the Tennessee. He was also an early member and supporter of the Illinois Press Association, and traveled to some of their conventions and on their outings. He was once a vice president of that organization.

Before the civil war, politicians from Bunker Hill and Girard and Virden tried to separate Macoupin into two counties, taking in parts of Madison and Montgomery, but that action came to a halt when war broke out. Immediately after the war, and soon after Hedley became editor, to prevent this separation, Macoupin county officials began building the million dollar courthouse. There was a great deal of controversy over its construction and the huge cost overrun. Originally budgeted at $250,000, before it was finished it cost nearly $1,500,000 and it took county residents 50 years to pay it off.

Hedley protested loudly through his paper, giving column after column to the cause, but to no avail. His first reference was made in the Feb. 21, 1867 issue, when he referred to "the Court House Clique". It was ever after referred to as the "court house swindle".

Macoupin County's most famous son is probably James M. Palmer, who grew up south of Bunker Hill before there was a Bunker Hill. While Palmer was governor of Illinois he signed legislation to allow the completion of the court-house at Carlinville, and ever afterward he was a bitter enemy. Hedley never forgot it, and was still harping on it 30 years later.

As busy as he already was with his newspaper and other activities, in 1872 Hedley was appointed postmaster at Bunker Hill. He was put out when the Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected president, but on the election of Benjamin Harrison in 1880, he was re-appointed. He edited the newspaper himself while holding his job as postmaster.

Of course he had good help or he couldn't have done this, but his hand was evident. There were few misspelled words and no bad writing in his paper; but that changed immediately after his departure. He had an equally qualified assistant at the post office.

So you can see, Hedley was a busy man. He and his wife had twin sons, who both died, as did a daughter. They had two daughters who survived to adulthood. His wife died and he remarried. He found time to write his book, and to travel extensively as a speaker following its publication.

That Hedley was well thought of locally was made evident in 1882 when a group of men representing about a hundred Bunker Hill citizens called on him at his house in the evening and presented him a beautiful French bronze clock and a pair of elegant bronze statuettes.

But it is only natural for someone so opinionated and so active to have enemies. Bunker Hill always voted Republican, but the Democrats won all county elections, just as today. Hedley got along with the Democrats all right, although in the 1880s they started an opposition newspaper. It never did well as long as Hedley owned the Gazette. After that it was a different matter.

So the years rolled along until 1897. Hedley's daughter was working with him at the Gazette, and he was no longer postmaster. He wrote as a free lance contributor for a St. Louis and Chicago newspaper. He was now in his 50s.

About 1894, a man by the name of J. R. Richards retired from business in St. Louis and came to Bunker Hill, where he had relatives. He was a big man, standing six feet tall and weighing 250 pounds. He was described as a rich man who gave generously to the local causes. He bought the local foundry, which was failing. He bought the Monument House, an elegant hotel, and refurnished it, installing his cousin's husband as manager. He built a magnificent three story mansion and an electric light plant to light it. He sold the excess power to some local businesses, the first electric lights in Bunker Hill.

He also fell in love with his cousin's daughter, Ella Brown by name. She worked for him as a secretary, although there really wasn't much work for her to do. He gave her expensive jewelry and other gifts instead of a salary, and gave her parents a place to live and her father a job as manager of the hotel. He proposed marriage time after time, but she would not have him. After he was in town about three years, he ran for mayor, and was elected by a huge majority.

At first he and Hedley were friends, but they had a falling out over an electric light franchise Richards wanted.

Among the many activities I failed to mention was Hedley's position as organist for the Congregational church, and later choir organizer and director. The church had a new pipe organ installed and Hedley was the organist.

Since Hedley was away so often, it was deemed advisable for another person to be trained as organist, and the lot fell to Miss Brown, with Hedley her instructor. She and Hedley spent considerable time together, both at the church and at the local furniture store, which in addition to being a mortuary, sold pianos and organs. The two spent considerable time together there in the music room.

Some of the Congregation-alists complained that Hedley and Miss Brown were sometimes at the church together alone, and on more than one occasion, it was said the door was locked from the inside.

Whatever was going on, the jealous mayor believed the worst, and was determined to protect Miss Brown's good name. He made threats in the presence of others that either he or Hedley had to leave town, and it wouldn't be him. On more than one occasion he threatened to kill Hedley. He always carried a cane, and on two occasions, on meeting Hedley on the street, struck him with his cane.

Hedley submitted to these without comment. Some said he had lost his courage, while others thought it was to protect Ella Brown's good name.

Townspeople became concerned and got the two men together and made them sign an agreement to be civil to each other, and to speak when they met. It also stipulated that Hedley should not see Miss Brown or speak to her except to greet her if they met on the street. Both men signed the agreement, but Miss Brown refused. One account says when refusing to sign, "she stamped her pretty foot".

A couple of months after this, on June 12, 1897, the town being a small one, Hedley and Richards met on the street in front of McPherson's hardware store. Richards angrily asked Hedley why he hadn't spoken to him as stipulated in their agreement. With that he raised his cane to strike Hedley, who lost his hat, either from the blow or from dodging it.

At that point, Hedley drew a pistol from his pocket and shot Richards twice. One bullet struck him in the arm, the other in the stomach.

Richards was taken into the store, and later moved to his home, where he was attended by two local doctors.

Richards had insisted that if anything ever happened to him, someone was to contact a Dr. Mudd of St. Louis. The St. Louis surgeon was summoned and sped to Bunker Hill by special train. He arrived in record time, but to no avail. The foundry noon whistle was blowing when Hedley and Richards met in front of the hardware store. When the six o'clock whistle blew, Richards was dead.

After the shooting, Hedley ran home, threw down his gun, hurriedly told his wife what had happened, and then sped to a minister's office.

|

St. Louis and Chicago newspapers made much of the shooting of the mayor by the editor, and of the beautiful young woman the two old men cherished. The rival Bunker Hill News was nearly as bad. (She wasn't really that beautiful. She was described as "comely" by some accounts.)

At this time Hedley was 53 (he was 54 the day he testified during his trial) and Ella Brown about 35. Richards was 65. He had never married. He wasn't physically attractive, but had a high opinion of himself. He didn't think Ella could do any better than to be his wife. He was believed to be wealthy, but after all was over, his estate was bankrupt. His foundry and hotel brought hardly anything when sold at the auction settling his estate. He was mayor for less than three months before his death, but he will ever be remembered as the mayor of Bunker Hill who was shot to death by the town editor.

The sensational news coverage continued during the trial. All the lurid details were brought out. When it was over, Hedley was found innocent.

He resumed his newspaper work, and continued writing his column. But in 1898 he announced his departure from Bunker Hill to write for the St. Louis Republic. His last article in the Gazette, consisting of one short paragraph, appeared in the June 1, 1898 issue. This lacked just 13 days being one year after he shot Richards.

It was said by some in Bunker Hill that Hedley was run out of town, not for killing Richards, but for his involvement with Ella Brown. He lived in St. Louis for a time, then in Kansas City and finally, Brooklyn, New York. In the meantime, his wife divorced him, charging adultery, and he married Ella Brown.

Hedley was commander of the GAR post in Brooklyn, and died in Brooklyn Jan. 7, 1924 at the age of 79. He was buried in Cypress Hill Cemetery in New York. At the time of his death, he was an editorial writer connected with the Lewis Historical Publications Co.

After Hedley left Bunker Hill, the Gazette changed hands and then it went down hill until in 1905 it was bought by the rival Democratic Bunker Hill News, the stipulation being that the older newspaper was to be named first, thus the present Bunker Hill Gazette-News.